B Plot

War—the ultimate conflict when communication has broken down and words have given way to violence. Many romances are set against the stage of war with military personnel as main characters and violent armed conflict as the background.

War settings have the ultimate stakes for the individuals and society. Violent armed conflict poses immediate risks to the lives of the characters and their loved ones. War jeopardises livelihoods and the economy.

In situations in which war is the driver of the economy, there are trade-offs for the characters. They might pay higher taxes, have fewer social services, or not be able to pursue their aspirations because their labour is redirected to the war effort. Their might also have been jobs in the war machine that would not have been available otherwise. Jobs in armament factories where people made friends, found love, and career advancement.

War also creates high-stakes moral dilemmas. To what degree, if any, does a society give up some of its freedoms (blackouts, curfews, rations, and so on) to support a war effort? To what degree are individual rights curtailed (a military draft or redirecting labour to produce armaments) to support the war effort?

These high-stake questions amplified personal and interpersonal conflicts and dilemmas.

Love in a time of war highlights the capacity for both compassion and savagery in individuals, and those emotional contrasts make for a terrific story.

Consider a FMC who doesn’t pay attention to international politics. An enemy attacks her country, and she joins the military to defend it. She is at odds with her brother who insists it’s someone else’s problem. She is at odds with her love interest (LI) who wants to start a business with her. She is at odds with her family, LI, and friends who don’t want to see her injured or worse, killed.

Navigating these complex relationships tests resolve, strengthens some relationships, and destroys others. Maybe the LI doesn’t have the stomach to wait for the FMC to return or they have painful memories of a family member who was killed in another conflict.

Love in a time of war is both uplifting and crushing. Social norms can be relaxed or tightened, changing how people form and maintain romantic relationships. Relationships might be formed quickly because both parties fear death and want one last good memory before heading off to the front. Relationships might be harder to form because of travel restrictions, rations, roadblocks, and other impediments.

What is love in a time of war?

Is it one last romp to seek some pleasure?

Does it afford opportunity for introspection?

Does it unite people who normally wouldn’t associate, in a common cause?

What happens to those relationships after the war?

Do they stay together, or they disintegrate?

War, like romance, risks everything and loses or gains it all.

How do your characters act during war? Let me know @reneegendron on Twitter.

Thank you @Sstaatz for the topic suggestion and @Joa70 from Pixabay for the image.

Twelve years ago, I decided to write again. It was a hobby at first, but as my writing and stories improved, I gave serious thought to publishing. At first, I thought traditional publishing was the route for me, but I knew the odds of being published were slim.

I attended several author conferences to learn from experienced writers. I attended panels where agents described what they were looking for in an author. I attended sessions in which panellists were representatives of small presses, and they were extremely candid in explaining their resource constraints. A small Canadian press owner said he wouldn’t publish an author if the author had already self-published the book. I asked why. The owner said the author had already taken his customer base away, the author’s friends and family.

I was stunned by their response. The small press expected to sell 15-25 units. While it’s unlikely an author will make a full-time income selling books, it seemed to me an established press (with its newsletters, social media, connections, etc.) should be able to sell more than 25 units.

Or, I should say that a small press should have a goal of selling more than 25 units. They shouldn’t stop trying to sell once the author’s sold it to their friends and family.

The other representatives of small presses on the panel agreed with the person’s assessment of not taking on a self-published book.

That conversation left me with a lot to think about.

I was leaning towards indie publishing at this point because my fantasy romance series is 29 books. No publisher will agree to a 29-book series from a no-name author. And worse yet, a publisher might agree to the first three books but not the entire series, leaving fans hopping from one publisher to the next looking for the series. And my nightmare, the first book is picked up by a publisher, and they control whether the rest of the series is published for the next seven years.

One key takeaway from these conferences is that writing a series is easier to sell in the long term than writing a stand-alone book. Indie authors at these conferences say a series provides a higher return on investment in marketing dollars because if a reader picks up book four and likes it, they’ll likely order the first three.

That works in my favour because I like to write long arcs that can’t be contained in one book.

I participated in other conferences that had representatives from larger publishers on panels. One panel discussed the importance of authors self-promoting their work because publishers don’t have the budget to market their books. Many publishers no longer pay for author tours, and it’s up to the author to organise blog tours, pay publicists, and attend book shows.

If the author’s expected to put that much effort into marketing, I’m leaning towards keeping more of the royalties to compensate for that work. Most publishing companies don’t budget on their percentage of royalties. If you have an agent, additional percentages are directed to the agent.

A publisher said they receive over 6,000 submissions for 48 slots. Of those 48 slots for new books in one year, 12 are already earmarked for a specific series. That leaves 36 books that the publisher would be open to considering books. Of those 36 books, the publishing company leans heavily in favour of authors they’ve worked with before.

The editors are swamped with submissions which is why most authors receive a form rejection. The editors don’t have the time to provide individualised feedback.

Finding these calls and submitting the proposals (which have to be tailored to each publisher) seems like a lot of work for a low acceptance rate.

Traditional publishers and agents are the way to go for many authors. Publishing companies and agents offer unique value-add to a large swathe of writers. Many writers prefer to leave the business stuff to professionals and focus on writing their next book.

That’s okay.

What I’m presenting are my experiences and perceptions.

The first year of COVID did something to my brain. I couldn’t write fantasy romance anymore. I had started the first four books of a series fantasy romance series, but I couldn’t continue with them. At least, not at that time.

I switched from writing exclusively fantasy romance to other genres including contemporary, historical westerns, and sports romances, to jumpstart my writing. Someone tagged me in a call for a book submission as part of a common-world series. Multiple authors would be writing books based on the same world, and their characters could and would interact with one another.

It was an interesting concept and in a new genre. I had never submitted to a publisher and figured it was worth this one shot.

I submitted an outline, and it was approved. I wrote the piece and submitted the first three chapters. I was thrilled when the editor asked for a full manuscript, which I promptly submitted. The editor came back to me with suggestions on improving the text and said she’d be willing to review the entire manuscript again.

I was excited to receive such coaching and advice from an editor at a respected mid-range publisher in the United States. I know several authors who have published with this company and were extremely pleased with their experience. I reworked my manuscript and resubmitted it. It was turned down.

I could have lived with it being turned down. However, the editor said it wasn’t a fit for the common-world series and then directed me to a fee-for-editing service at the same publisher. I perceived the common-world series as a hook to attract different (new to the publisher authors) and then direct them to their paid editing services.

Whether that was the publisher’s intention or not, that’s how I interpreted the situation. It left me more convinced that Indie publishing was the way for me. I control the costs and the production schedule and have full creative oversight of the cover, marketing, and social media posts. I also have direct control over how much advertisement I spend and when.

I’m always learning and honing the skills needed to be an indie author. I regularly take writing courses to improve my craft. I participate in a professional writers’ association and attend conferences. I listen to writing-related podcasts and learn about marketing, social media, and different mechanisms that successful indie authors use to keep their content fresh, balance writing with running the publishing business and keep to a production schedule.

I learned about the broader indie author ecosystem and the services available to support an indie author. These include low-cost cook cover options, editing services, video trailer services, and a host of other supports for successfully launching a book.

By no means am I suggesting you sink 10k in a book launch. I take the grow-steady approach, where I grow my following/readership over time. All money I make from writing gets reinvested into marketing. I have strategic marketing campaigns, and I look for no-cost, low-cost ways of advertising. I engage in review swaps and so on.

The group 20 books to 50k offers great marketing insights. This group is tightly moderated. It’s best to sort through their archives before asking a question (as the question will likely not be accepted by an admin). They have a yearly conference in which most sessions are viewable through Youtube.

Years ago, I decided to be a writer. I didn’t know which route I would take, but as I engaged with the market, it became clearer that indie publishing was my way. Will I think that way in five- or ten years? I don’t know. But for now, indie all the way.

Thank you @LouSchlesinger for the topic suggestion.

Readers are encouraged to reach out to me on Twitter @reneegendron

I struggle with time jumps in my writing. My characters travel from point A to point B on a mission. Watch any movie based in large metropolitans such as London, New York, or Tokyo, and they show the characters in a car or on a subway. They get to their destination in no time while commuters familiar with those cities laugh or cry at how easily the MC moves around. Writers engage in time jumps to speed up time. The one exception to this was the show 24, where events were portrayed as they occurred.

Earlier in my writing journey, I wrote every detail of my MC’s journey, which was mind-numbing for readers. No one wants to read about how every meal is hunted and prepared or how the MC didn’t sleep well because they slept on the ground. Okay, okay, okay. You can write about every little detail if you’re Tolkien. I, however, am not Tolkien, and my readers aren’t as tolerant of slow pacing.

It’s okay to put details in if it advances the plot. If you spend time (words) describing a meal, how does that meal deepen characterisation or highlight a conflict? If your MC eats something new, do they have an allergic reaction or get food poisoning? How would those situations advance or hinder your MC’s ability to work towards the book’s goal?

There are many shorthand ways to speed up the pacing of your story. There’s the dialogue slip-in where one character mentions it’s a two-hour drive or a month-long boat voyage. The reader has a sense of the length of travel without being burdened or distracted by it.

Another shorthand is to deepen the POV. Show your MC’s blistered-covered feet and the hole in their shoe from a three-month hike across the country. There are other creative ways of showing the passage of time—adding or losing weight, greying of hair and/or presence of wrinkles, changes in the terrain (the last time the MC was home, there was a river running through the property, now the river has dried to a creek), changes in season, mentioning a character’s birthday (the story starts with a three-year-old-MC and there’s a jump to their tenth birthday), and so on.

All these approaches to the passage of time can be boiled down to one sentence or expanded into pages of details (provided they advance the plot or deepen characterisation).

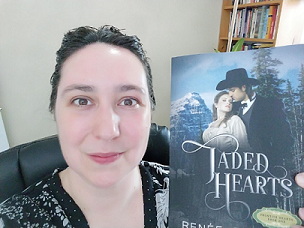

Here’s an example of a time jump from my western historical romance, Jaded Hearts.

Bertram’s POV and these are the last sentences of chapter 2:

Bertram grimaced. Da’s past threatened to rob his future, and it wasn’t even noon.

These are the opening lines of chapter 3 in Ruthanna’s POV:

Ruthanna sat in a high-backed chair in the dining room of the Anderson Hotel. The dust from her travels washed from her face, but the fatigue of her journey still weighed on her body.

I used a chapter closing to have a half-day time jump.

Here’s another passage of time from Ruthanna’s POV:

Sucking in a large breath, she dug deep inside her to the little Ruthanna, who was dragged from mining camp to mining camp on a moment’s notice without a proper breakfast or full night’s sleep. Twenty-six-year-old Ruthanna found the strength of five-year-old Ruthanna always had and pushed herself to her unsteady feet. Her heel caught the hems of her skirts, and she stumbled backwards, crashing on her shoulder and bashing her head on a boulder.

Something cracked. Bone, brain, both.

Her tongue rolled back in her throat, and she choked. Her mind fled to somewhere dark and throbbing and senseless, but her body rushed to the rescue, rolling her to her side, forcing a sputtering cough from her lungs.

Time passed.

Minutes. Hours. Geological.

Agony dragged her away from death to awareness with a steady pounding beat against her skull.

Here’s an excerpt from Seven Points of Contact:

Dad grunted, the same grunt when he was onto something, but willing to keep it a secret—for now.

By the end of the first game, the colour of Dad’s cheeks had drained to a sickly pallor reserved for dead fish. He hadn’t touched his can of Ensure, but he had settled deeper into his chair and closed his eyes.

Jonas was three years old again, wanting but unable to help with adult problems—offering a cookie when surgery was needed. “You want me to stay?”

I could have given a hand by hand (they’re playing cards) description of how Jonas’ father is waning, but that didn’t serve the plot.

Another example from Seven Points of Contact:

Miranda finished her reports for the day.

*

I could have gone into the minute details of a car loan application, but it didn’t deepen characterisation, advance the plot, or add conflict.

Shorten moments (fewer words) when nothing of significance happens. Expand moments of time (give them word count) when they demonstrate conflict, strong emotion (characterisation), are a key learning point that the MC might not yet learn or present an obstacle. Well-crafted time jumps ensure good pacing and reader engagement.

Thank you, @LouSchlesinger, for the topic suggestion.