B Plot

Throughout my life, I’ve written a lot. I started writing historical fiction, poems, and fantasy. All of the words were, quite frankly, flat. I turned my attention to romance about seven years ago, and my stories improved. What follows is my opinion and my opinion only and keep in mind that I write 50% romance arcs and 50% non-romance arcs. As someone from my writing club recently mentioned to me, he was surprised that I classify myself as a romance writer because of all of the non-romance things in my books.

I think there’s stronger character development when a romance arc is included. All romance books have two layers of development. The first layer of development occurs at the character level. If there is one POV, then that character must address and overcome personal trauma or internal conflict before they can turn their attention to their romantic counterpart. If there are two POVs, then both characters must have personal insights to address individual problems.

When part of the book focuses on the internal character development, the character seems fuller and more relatable (at least to me). Everyone has been hurt. There’s at least one childhood event that still stings or makes you ashamed or impacts you to this day.

Maybe you were told you had to be perfect and came to the brutal (but liberating) realisation that you aren’t perfect (as all humans aren’t perfect). In trying to be perfect, you overwork, you stress, you surpass expectations to the point where other people don’t want to work with you because you make them look bad.

Maybe you were told something about your appearance and have struggled to accept and love yourself for your inner and outer beauty.

Whatever hurt, you left a mark. It’s the same with characters in romances. They need to work their way through whichever trauma or pain and earn their happily ever after.

The second layer of conflict is what keeps the lovers apart. A difference in politics, socio-economic classes, life goals, etc., must be overcome and reconciled before the couple can have their happily ever after.

This leads me to my next point. I enjoy writing stories with happy endings. A romance can have a happy-for-now ending, but most end with a happily ever after. If the ending is sad (a tragedy), then it is not a romance. Instead, it’s a love story.

There are many options when writing external conflict. There’s the conflict between the lovers that keeps them from their happily ever after. There’s the non-romance conflict. What are the characters doing? Are they going on a quest and have to battle horrible weather and harsh terrain? Are they at a ball where they need to navigate politics and social norms and gossips and competitors for a lover’s attention? Are they marching off to war to face an ancient enemy?

The non-romance arc (even in traditional romances, there is a non-romance arc) is both an independent and dependent opportunity for character and romantic relationship growth. In traditional romances, the non-romance arc has fewer words dedicated to it. Again, I strive for 50/50 romance and non-romance arcs.

By independent opportunity, I mean each character faces unique challenges. They must learn a new skill, adapt to circumstances, or defeat a foe. The characters must also learn to cooperate and grow as a couple. In the non-romance arc, characters test their resolve to help the other, develop the relationship, and cement the fact they are a couple.

I find these textures of conflict interesting to read (well, listen. I listen to 99% of my books) and write. I enjoy writing the nuances of how a similar deep hurt (let’s say low self-esteem caused by body issues as a teenager) manifest differently in adults. Each character is unique in their efforts to overcome.

Romances pair well with every genre. You can have a romantic medical thriller, a romantic fantasy, a romantic dystopian cli-fi. Name the genre you and can always pair it with a romance arc.

I write a lot. A _lot_. More than 2.9 million words, a lot.

I promise my readers a new story (not written to formula) each and every story. With the diversity of romance tropes and the ability to plug it into any genre, I find it stretches my writing scope. Combining different tropes (romance and non-romance) across genres flexes my writing skills and helps me create unique situations.

Romances can speak to the human element. They speak of deep heartaches, misery, overcoming trauma, and finding a way to live a full and enriched life. And, I have to admit, writing the sexual tension between the characters is fun.

What do you like about romances?

Reach out to me on Twitter @reneegendron

Thank you to @DanFitzWrites for the topic of this blog.

Before I share my editing process with you, let me start with the caveat that I’m not a line editor. I can’t tell a dangling participle from a gerund. The process I’ll outline below is my process. You have no obligation to try it or force your way of thinking into the holes and squares I’ll describe.

For me, the editing process starts with the outline. I’m an extensive plotter. I need to know how the story ends before I start. My outlines are point-form and run 50 to 100 pages. Each outline is broken down by chapter, which indicates the POV, the central emotional, character and plot beats, conflict, and dilemmas that character faces in that chapter. I then go point-form the action, scenes, and bits of back-and-forth dialogue for each chapter.

I must know the deep hurts of the characters, some of their back story (though I will discovery write quite a bit of their back story and learn about the characters as I write), and what keeps the lovers apart.

I’m a romance writer, and my stories always have at least two layers of conflict.

The first layer is internal. These are past personal traumas unique to each character that make them unable or unwilling to enter a romantic relationship. These traumas are also obstacles to the non-romance plot. For example, a character might have been spurned by a previous lover, and they are reluctant to trust in the romantic sense and trust the other person to help them resolve the non-romance plot.

I write 50% romance and 50% non-romance arcs, and that means my characters are busy. They are solving mysteries, going on adventures, spying, beating back an enemy, ruling kingdoms, and generally doing good things for the sake of doing good things.

The second layer of conflict is what prohibits the characters from a romantic relationship. Sometimes this is dependent on solving internal conflicts first. Other times, it’s an antagonist, different beliefs, societal expectations, or other constraints the characters need to navigate and reconcile before solving the romance and the non-romance arcs.

Once I have the non-romance trope, and the romance trope sorted out, I write. [I will prattle on for hours and/or pages about tropes, but I will refrain from doing so on this blog post. I hope you appreciate the restraint I’m exercising. However, if you want to listen to me talk about tropes and mechanics, you can do so here].

My first drafts are full of bobbleheads and Cheshire cats. My characters smile at everything—drying paint, the pattern on the rug, the dust in the wind. Why? For me, a smile or a grin or a curved cheek or a twist of the lips is a place holder for an action that has meaning for the character. Meaning for a character could be a mannerism, a reaction to dialogue, an internal thought, observation or something that deepens characterisation.

Let’s take the original sentence of a western historical romance I’m writing. Below is the first version:

Before: Ruthanna released a slow breath. Nerves. Bertram was shy. She smiled inwardly. A bad encounter with a business associate added to the weight of being shy. A sliver of hope to meet the man from the letters.

The words don’t pop off the page, but the reader understands the character is nervous about meeting a woman. There’s a smile, but it doesn’t mean anything. It doesn’t add emotion or characterisation.

On my second edit, I changed the passage to:

After: “Meaning what?” Maybe Bertram was shy. Shy types always did better in quiet settings. Shy types had their allure.

It’s a stronger sequence because we know her thoughts, and there’s a touch of sexual tension between her and the man she’s having dinner with. She’s willing to give him a chance because she’s intrigued by him.

With the first draft done, my characters need to visit the chiropractor for all of their bobbleheads, and they need to take elocution lessons because they all sound the same. That’s fine. It’s part of my process.

What concerns me most in the first draft if is the pieces fit. Do my chapters have strong hooks? Do my characters face enough exciting and complex problems that drive the story? Is there enough sexual tension between the romantic leads? Are there any sagging bits or places where I’ve wandered too far?

I’ll usually recognise those places as I’m writing and make notes to correct them on the second draft.

If writing is all that I do for the month, I can write an 80-100k novel. Is it in good shape? No. Is it better than the drafts I wrote a year ago? Yes. Why? Something about practice making things better. That, and black liquorice and beer. Again, that’s another post.

I’ll let my second draft sit and work on the draft of another story. Weeks, sometimes months later, I’ll revisit it. Sometimes the edit is after an alpha reader (a person who reads the first draft of a novel to critique the direction and tone of the story and not the prose) and points out major plot holes and boring characters. That’s what I ask of alpha readers. Does the story, no matter how poorly worded, work?

On the second draft, I set to the task of improving prose, eliminating bobbleheads and nervous twitches (which in romances tend to be smoothing skirts or eyebrows. At least my romances on the first-go-round). In the second draft, I’ll infuse differences in speech, bring out the internal conflict and dialogue more, and focus on sharpening the banter. I try, sometimes succeed but often fail, at increasing the tension in dialogue. Sometimes, I’ll write jokes.

In the second draft, I’ll focus on backstory. Over seven years, I’ve written 34 books, none of which are published. That said, I’ve gotten better with the years and the millions (no word of a lie—2.9 million words written, excluding drafts of the same book) of words I’ve written at reducing back story. Right now, in the first and second drafts, I’ll have three to four sentences of backstory. This means I’ll not infodump or write a character’s autobiography. I keep a character’s backstory short and sweet.

Example:

Almost thirty years of marriage and Mama never once mentioned demanded Pa greet them at train stations or keep his appointments with them. Not one word of disappointment, not one angry look, not one dinner spent in silence. It was always smiles that reached unhappy eyes, and ‘yes, dear’, and ‘we’ll make the best of it’ and let’s drag out trunks across the mud in search of Pa’s tent.

That passage comes at the 25% mark of a western historical romance. What does that passage say to you? Does it show why the woman is reluctant to enter a relationship with the man? Does it show why the woman wants to retain her financial independence?

I’ll keep tweaking those sentences to see how much further I can condense them while retaining their emotional power. Emotional power is defined as relatability with the reader and insight into character.

During my revisions, I’ll see if those are necessary or if they need more power.

Then the story is off to the beta readers to check on transitions, hooks, and intrigue. There must be appealing sexual tension between the characters, and there must be tension in the non-romance plot. The readers need to have some degree of nervousness about whether the characters will achieve their non-romance goals.

It then becomes a cycle. The more I write and study craft (yes, I take lessons from NYT and USA Today bestselling authors, writers who have more talent and skill than me, and workshops through professional associations), the better (I hope) I become. Yes, that sentence was wordy. Yes, I need a line editor. Yes, I’m a work in progress.

I cycle through beta reads, courses, and my versions until I develop a finished product. When I have a finished product (to my non-line-editor-eyes), I put it on the shelf and save it for professional line edits. I haven’t yet reached that point, but I sense that 2021 is the cusp. My goal in 2021 to have one full-length fantasy romance novel (A Gift of Stars) professionally editor and released. My stretch goal is to have a second book (western historical romance or contemporary romance) professionally edited and released by 2021.

Here’s to lofty goals, strong sentences, characters with purpose and poise, and hooks that keep the readers flipping pages.

What is your editing process? Reach out to me on Twitter @reneegendron for a conversation.

The question I received from @LouSchlesinger that inspired this piece was about an overall editing process.

What Makes a Modern Romance Trope?

Tropes. Romance readers love to read them and romance writers love to write them. A trope is a common plot element that is easily recognisable. Fans love them because they know what to expect in a story. If you see a picture of a woman in a puffy silk dress with her hand on the chest of a dashing man wearing a brocade waistcoat standing in front of a castle, you know you’re in a for a historical romance—most likely Regency. Regency romances are set during the British Regency period (1811-1820) or early 19th century.

Romance relies heavily on tropes to inform the reader what to expect. Some writers spend their career writing one or two tropes. Let’s see if you find any of these tropes familiar:

- Enemies to lovers

- A second chance at love

- The girl or guy next door

- Agents dating where the leads are spies or police officers or other law enforcement (customs officers, game wardens, etc.)

- Highlanders

- Marriage of conveniences

- Marriage of necessity (to protect someone)

What makes these tropes modern? The first thing is agency. Agency refers to the degree of a character’s willingness to make decisions and take action to shape their futures. A character with a high degree of agency sets a goal and works towards it. Do they always achieve the goal? No, but they engage in appropriate behaviours to reach that goal. A character with no agency has things happen to them and makes no effort to improve their circumstances.

Historically, many romances had one lead character, and usually the woman, lacked agency. This was particularly true in historical romances where the female lead needed and waited to be rescued. She batted her eyelashes and smiled when she was told to marry the hero, and things happened to her. I found this trend to be particularly true in many books until the mid-2000s when both main characters started having more agency. In many ways the lack of agency was unrealistic. Historically, different constraints and pressures were imposed upon women and they did not have the same opportunities for education and careers. However, women were active in their communities, they had independent thought, desires, perspectives, knowledge, and spheres of influence.

How do you give your characters agency? Give each main character personal goals. Each main character needs to have a life outside of the romance. They need past hurts, dreams, obstacles and resources to draw from to address their goals. The more they address their goals, the better head and heart space they are in to participate in a healthy romantic relationship.

A second way to give your characters agency is for them to push back against abuse. Whether it’s emotional neglect from parents, a bully of an older sibling or neighbourhood child, a soured first love or some other deep personal trauma, there comes a time when each main character needs to push back. They might be encouraged by their romantic lead, but they need to decide to stand up for themselves. Pushing back against abuse are great scenarios for try/fail cycles. On the first attempt to be assertive, things don’t go well. The character learns, improves, and tries again—something shifts. The abuser pushes back harder. The cycle continues until the character breaks away, realises they can’t change the abuse and comes to internal terms, or rebalancing the relationship based on mutual respect.

A third way to give your characters agency is to give them meaningful decisions. Give them problems and dilemmas that force them to choose between path A and path B. Let’s suppose Emily wants to go to university. To study hard and get the grades she needs for a full scholarship, she needs to stop playing lacrosse after school. She loves lacrosse and hopes to become a professional player. She’s good enough to make the pro leagues but won’t earn enough money to support herself as a professional athlete. If she studies, she has to give up something she loves because none of the schools that offer her program of choice has a lacrosse team. No sports scholarship for her. The decision she makes will have repercussions on her future and create different life strategies.

Remember, some decisions can’t be undone. They will haunt or buoy a character for the rest of their lives. Make sure that each character has at least one critical personal choice to make for their personal goals and one critical choice about the relationship. Generally, the more meaningful choices or dilemmas you give a character, the more robust their arc. Romances are driven by character development, and romance readers relish personal struggle and triumph.

Individual Goals. Decisions with consequences. Dilemmas that alter the future. That’s what makes any trope modern.

How do you give your character agency? Feel free to reach out to me on Twitter.

I want to thank @SStaatz for the topic suggestion.

It’s a long title, I know. I’m used to writing 80,000-100,000-word books, not catchy marketing slogans. Bear with me. I promise the article will be more interesting than its title.

In a previous post, I discussed the importance of conflict to keep the reader engaged. I also mentioned that a conflict evolves until the character learns to address it or fails, and the book ends in a tragedy.

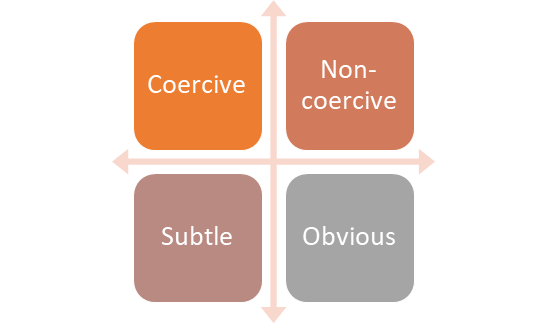

Let’s turn our attention to power. Power can be coercive (use of violence and threats of violence to achieve a goal). Power can be non-coercive (a person held in high esteem in a community may make requests, and a person fulfils them out of their own volition). Power can be in your face (soldiers from an invading army marching down a street). Power can be subtle (your sister has your parents wrapped around her little finger no matter what she does).

Power can be harmful, and it can be empowering. It depends on the wielder of the power and what they do with it. Let’s consider a nine-year-old MC who is bullied. The MC can use coercive power to stop the bullying (punch the bully in the face). They can use non-coercive power (reason with the bully, tell their parents, or inform their school principal). Here’s where power gets interesting. The nine-year-old can ask to arrange circumstances for other, larger children to be present the next day to protect them (subtle use of power). Or the MC can walk home with their two older siblings (obvious use of power).

Power is an essential concept in writing because it’s the consequence of a conflict. Let’s take a look at Star Wars. A group of rebels fight against an oppressive government. The empire exerts power in all four ways mentioned. The obvious ways are violence and coercion. It’s a war, and people fight and die. The empire also has non-coercive means of exerting its influence by paying people to give them information. The loyalty between the emperor and the Sith is also a form of subtle power. The relationship between Qi’ra and Han Solo is another form of non-coercive power that ends in tragedy.

To craft exciting characters and stories, all forms of power need to be applied. Why? Even in cases of evil empires and oppression, the oppressor uses different forms of power. Why? Using in-your-face coercive force uses an incredible amount of energy, time, and effort. I don’t understand the economics of the Star Wars universe. It seems every movie has massive rebel and imperial fleets destroyed without obvious means to replenish them (particularly on the rebel side where they are always running from secret base to secret base).

The more violent the coercion, the more effort it takes. Coercion doesn’t always mean physical force in the form of armies. Coercion can also mean verbal or social pressures. Think of Regency romances where many plots revolve around the ‘ton’ and the ‘ball.’ All eyes follow MC1 around the ballroom, waiting for them to make a mistake—drop a napkin, stain their clothes, speak out of turn, dance with the wrong person (social norms with high personal stakes). There are many backhanded compliments, people looking down their noses at someone, exclusion because they aren’t from the right background, and a lot of effort is put into gossiping and keeping on top of who was invited to which party. These factors combine to create social coercion or, in modern terms, the fear of mission out (FOMO). To assuage this fear, people conform. Often, great characters are the ones who resist social coercion and forge their path.

Remember, power takes energy and effort to exert. If you wonder why certain people were popular in high school, it’s because they worked at it. The popular set spent a lot of time interacting, showing up for each other’s events and activities, communicating, and engaging in each other’s lives. That’s a lot of work, but they get their rewards.

The MC has a conflict with someone or something. The antagonist (sometimes villain, but I’ll use the term antagonist) may be a person, alien, animal, or weather pattern. The antagonist uses different forms of power to realise their goal.

Let’s look at the example of a natural disaster. The first power exerted is violence. The flood or flow of lava forces people to move from a location they didn’t want to leave. Although a natural disaster doesn’t have intelligence or intent, it also exerts subtle forms of power. These forms include changes in temperature, which have consequences on the MC. A natural disaster also has subtle forms of power. A change in the river’s current can have other indirect consequences on the MC, such as introducing a new species in the waterway (perhaps sharks now swim in freshwater).

Power isn’t absolute. The rebels keep fighting against the empire. One spouse has more power when it comes to money, but the other spouse wields more power when it comes to family and friends. Your MC is excellent at work and is at the top of their game, but their personal life is in shambles.

Power is conditional and situational and ebbs and flows with a character’s personal growth (or regression), resources, knowledge, physical environment, and circumstances. Think of any movie in which two characters trade places—usually, a billionaire character trades places with someone poor. Due to the story’s constraints, the rich person no longer has that power and flounders like a fish out of the water until they reassert themselves, redefine how they manifest power, and regain control over their lives).

When you play around with both the MC and the antagonist’s type of power, you create fuller characters and a more nuanced world. Villains who only know how to punch are two-dimensional. MCs who only know how to appeal to authority (their parent, boss, police, etc.) miss growth opportunities.

Take a look at your WIP and sort through the types of power your MC and antagonist use.

- Does your MC rely on only one type of power? Why is that?

- Does your antagonist rely on only one type of power? Why is that?

- What can you do to flesh out different types of power in your WIP?

- What consequences do these new types of power have on character development, plot development and world-building?

Feel free to reach out to me on Twitter with your answers.

I’ll be putting together a series of webinars on conflict. If you’re interested in knowing more, please send me a note that says ‘conflict’. If you sign up to my newsletter, you’ll receive a free writing exercise. Be sure to put ‘conflict’ in the comment box.

We’ve all heard the phrase ‘conflict drives the plot.’ What does it mean?

We’re writers. Let’s start at the beginning. What is conflict? Conflict is a clash of rights, power, interests, processes and values. It’s something I want but can’t have. It can be violent or non-violent and oscillate between the two. A conflict that started over a difference in interests can shift over time and manifest as a difference in power and rights.

Conflict manifests in several ways, including internal (you have to overcome doubt), interpersonal between a dyad (you had a spat with your spouse), and inter-group conflict (such as gang warfare or war between nations).

How does conflict drive the plot? The main character must address specific problems, constraints, and dilemmas to achieve their goal (in a happy ending) or consistently fail to address these issues and fall further and further behind their objective (a tragedy).

A conflict must be complicated enough to have consequences on the story throughout the book. If a couple argues over what to have for dinner and becomes the book’s central conflict, the reader will disengage. Why? It’s challenging to keep a reader’s attention for 80,000 words when the couple is bickering over the same thing.

However, if the argument over what to have for dinner is symbolic of deeper issues, the author can mine the conflict and find deeper conflicts. For one partner, their internal conflict is shame at having an affair. For the other partner, their internal conflict revolves around forgiving the other person or leaving the relationship. Their interpersonal conflict (dyad) centres around a lack of communication and neglecting their relationship for years. Their group conflict may stem from family and cultural norms to stick to stay married no matter what.

In the above scenario, the couple cannot resolve the superficial issue of dinner until they address their individual conflicts. Why start with the individual? Ever think it’s easier to change the world than it is yourself? It’s like that with conflict. When people are in a high-conflict situation, they use their power (I’ll get into the concept of power in another post) to try to force change onto another. Sometimes they negotiate; most of the time, they use varying non-violent and violent coercive measures to get the other party to change.

When all of your characters’ attention is focused on changing the other, they miss introspection and growth opportunities. Without growth, there is no moment of insight that provokes a change of personal behaviour. Whether you are writing a plot-driven or a character-driven book, there are key moments in the story where the character needs an increase in awareness to resolve the conflict. Let’s take the movie Ender’s Game. A team of soldiers train to participate in a military campaign. The main character risks everything on an end-all strategy and wins. However, the main character has a moment of insight after his military win, which shatters his view of the war. The main character uses knowledge and drastically alters his behaviour.

If your characters are entirely focused on changing the other, they risk disempowerment. Why? They are not taking action to create the future they want to see and are not making the most out of whatever resources and opportunities they must shape their futures. For characters to be active, they need to make choices, execute the decisions, and address the consequences. When characters wait for others to change, they risk being pouty and whiny. A character can stomp their feet and stick out their lower lip for one scene, perhaps two, but no one wants to read about a petulant main character for the entire book. Adult characters shouldn’t throw temper tantrums because they didn’t get the soup of their choice. You get to use pouting or a temper tantrum once to demonstrate deeper problems, but you must move on to keep the story interesting.

There’s a dynamic interplay between internal conflict and the conflict dyad. Let’s explore this dyad a little more. MC 1 wants MC2 to do the dishes. MC2 refuses to do so, saying they have worked all day and are tired. MC1 has a choice to escalate the conflict and drudge up all of the past wrongs, and they do, and the conflict escalates into a shouting match and MC2 heading over to their friend’s house for the night.

Does that resolve the conflict? No. Did it make the conflict worse? Yes. Did it make the conflict more interesting for the reader? It depends on what happens at the friend’s house and how it gets worse for the individuals and the couple.

It’s two days later, and MC2 returns home. MC1 needs to use the car tomorrow because they have doctor appointments. MC2 objects because they have to travel to a rural area for their job, and they don’t want to drive across town at 07h30 to drop them off at their appointment early, then drive two hours in the opposite direction. The argument escalates. MC1 says MC2 was willing to find alternatives at the beginning of their relationship and slams the door to the bedroom. MC2 sits on the sofa and contemplates and recalls times when they were more accommodating and willing to find mutually agreeable solutions. Does it change MC2’s actions right away? No. It does spark a realisation in MC2 by comparing and contrasting who they were to who they are right now. The writer introduces more and more of these opportunities for reflection until the character is in the headspace to address the interpersonal or group conflict.

Ah, but you write plot-driven books. It’s the same dyad between interpersonal and group conflicts. When you are at war, there’s a learning curve. You need to understand your foe’s military strategy, their command structure, their objectives. Insight, in this case, comes from understanding what motivates them.

Information needs to be shaken loose for different decisions to be made. Moreover, the MC’s information must be internalised, and the MC must change their behaviour to achieve their goal.

Here’s an exercise for you:

- What is the central conflict in your WIP?

- What are three ways in which your MC(s) directly address the conflict?

- Are the ways your MC(s) addresses the problem the same? If so, how can you make them unique and more complex? Remember, your MC(s) is engaging the problem, and they should learn and get better (or worse)

- What are the consequences of their three approaches?

- Are the consequences of your approaches the same?

- How can you make the consequences more interesting to challenge your MC further and force them to learn a lesson before advancing to the next problem?

If you are interested in learning more about conflict and plots, reach out to me through my contact form with ‘conflict webinar’ in the text. I’ll be putting together a series of webinars.

Feel free to reach out to me on Twitter to let me know how you fared with the exercise.